Drawing inferences from facts.

A legal analysis of how South African courts draw inferences in civil disputes and criminal contempt cases, with case law and practical examples.

April 1, 2025

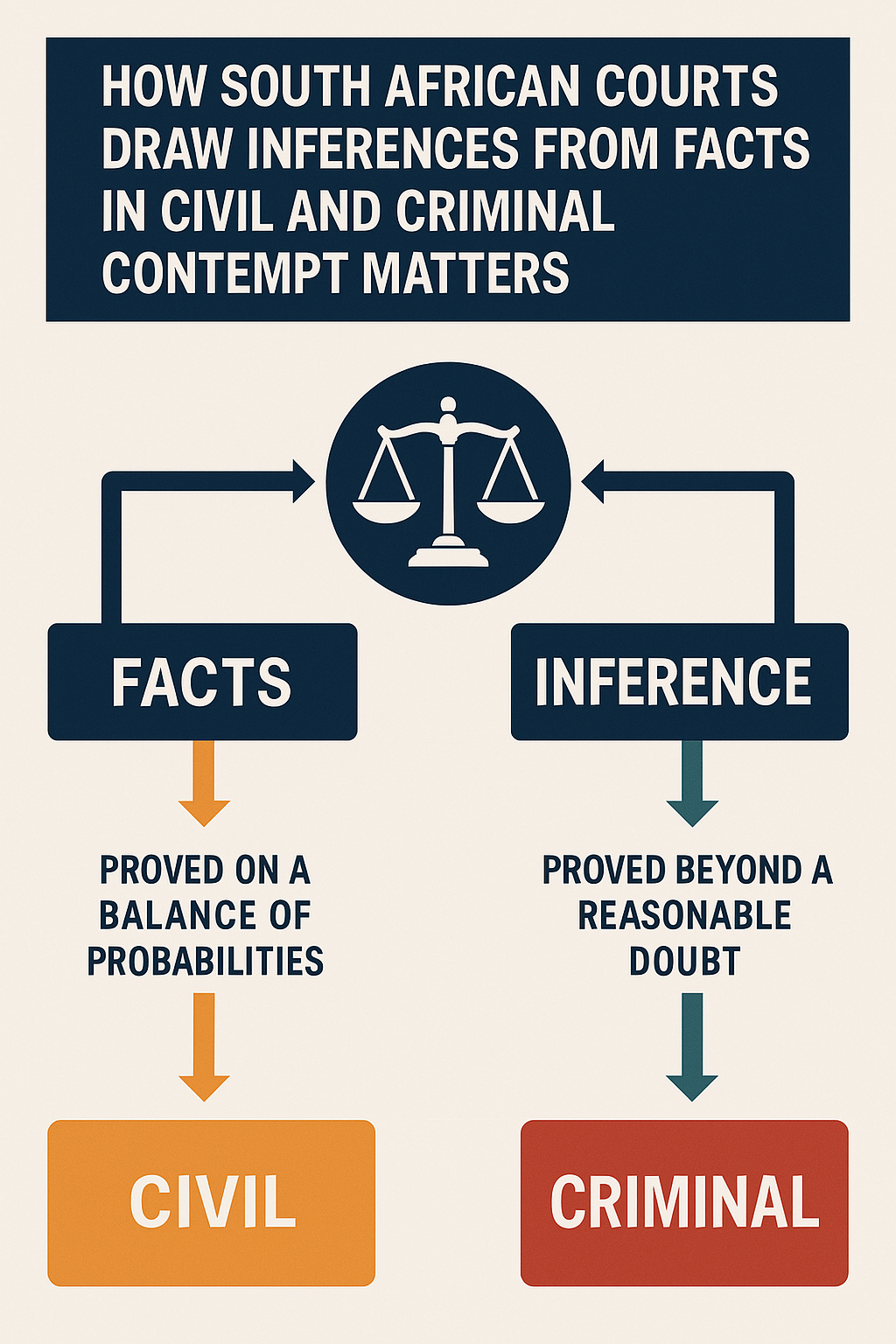

How South African Courts Draw Inferences from Facts in Civil and Criminal Contempt Matters

Introduction

South African courts frequently rely on circumstantial evidence—facts from which the court must infer further facts—especially when direct evidence is unavailable. The inferences drawn must adhere to principles that vary depending on the standard of proof: in civil cases, this is the balance of probabilities; in criminal or punitive contempt matters, it is beyond a reasonable doubt. This article explains the differences and guiding legal principles, with key case law to illustrate the approach.

Inferences in Civil Cases (Balance of Probabilities)

In civil litigation:

- Consistency with Proven Facts: An inference must align with all the proven facts (Briers v Salmon 2023).

- Most Plausible Inference: Courts may adopt the most natural or probable conclusion among several possible ones—even if it’s not the only possible inference (Govan v Skidmore 1952).

If two inferences are equally possible, the party bearing the onus fails.

Illustrative Case: AA Onderlinge Assuransie Assosiasie Bpk v De Beer 1982—the court used physical evidence to infer the likely point of impact. The inference was valid only because it rested on objective facts.

In Briers v Salmon, the court refused to infer negligence due to lack of sufficient objective facts about how the fire started.

Inferences in Criminal Matters (Including Contempt)

Criminal standard: Beyond a reasonable doubt.

Two cardinal rules from R v Blom 1939 AD 188:

- Inferences must be consistent with all the proven facts.

- The inference must be the only reasonable one—any other reasonable inference pointing to innocence must be preferred.

Illustrative Case: In S v Reddy 1996, the SCA confirmed that courts must evaluate the cumulative impact of circumstantial evidence, avoiding piecemeal analysis. The court found that the only reasonable inference was guilty knowledge.

In contempt cases, Fakie NO v CCII Systems (2006) is the leading authority. It affirms:

- Criminal standards apply where committal to prison is sought.

- Inferences of wilfulness must be the only reasonable conclusion.

- A bona fide misunderstanding can create reasonable doubt.

Judicial Cautions When Drawing Inferences

- Avoid Speculation: Inferences require a solid evidentiary foundation. Courts distinguish inference from conjecture (Rington 1989).

- Consider the Whole Picture: Especially in criminal cases, the combined weight of all facts must point to guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

- Inference vs Direct Evidence: Direct testimony may override inferences.

- Wilfulness in Contempt: Inferences of intent must be carefully considered and not based on mere non-compliance.

- Plausibility Matters: Courts apply a common-sense approach, rejecting fanciful theories of innocence.

Conclusion

The use of inferences in South African law is governed by careful reasoning, grounded in evidence. In civil cases, the most probable inference suffices. In criminal or contempt cases, guilt must be the only reasonable inference. Through cases like R v Blom, S v Reddy, and Fakie, South African courts maintain a balance between effective legal reasoning and safeguarding against injustice.

For legal professionals, understanding how and when courts draw inferences is crucial in both presenting and challenging circumstantial evidence.